At first everyone thought films were a novelty. Early distribution forced the theatre owners to buy the prints of films they were showing. This didn’t work out well for the exhibitors. As a result, it wasn’t a good business proposition to show a film.

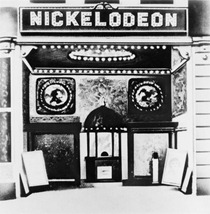

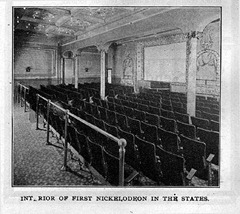

In 1903 the Miles brothers from San Francisco established the modern form of distribution by setting up the first film exchange. They bought the prints and leased them to exhibitors at a much lower cost than buying the film outright. As a result film became an economical win for everyone involved. This caught on rapidly. Nickelodeons sprang up all over the world and it was apparent film was here to stay.

People became hungry for new films, regardless of quality, and studios churned them out. As a result film didn’t change all that much. Between 1903 and 1912 there aren’t many noteworthy creative achievements or experiments – except for a few shorts by D.W.Griffith. What did change was the amount of film which could be produced.

But even if the filmmakers weren’t taking movies seriously, other groups were. Once the Nickelodeons sprung up and organised religion and the political right realised movies weren’t going away, they mounted campaigns to suppress them. Between 1907 and 1909 it became commonplace for minsters, politicians and business to be against the movie industry. Today it’s thought these campaigns were more economically than morally minded because people were frequenting Nickelodeons and spending their money there rather than at churches, saloons, and vaudeville theatres.

Another issue facing the early industry was piracy. There were no copyright law for “living pictures”. Exhibitors pirated copies of the films and showed them. Worse, since the equipment was patented and a fee was expected by those who used it, production companies were pirating equipment. Anything produced by that pirated equipment was considered the property of the production company that made it. So even the laws that did govern the industry were difficult to enforce.

In 1909, Edison and a group of patent holders created the MPPC (The Motion Pictures Patent Company) – a trust (a polite word for monopoly) that would try to control the film industry. Joining the trust was Eastman Kodak, the largest producer of film stock. The MPPC controlled who got equipment, who got film stock and who got distributed – at least in the United States.

What held film back, at least in the US, was that the MPPC believed film audiences had a short attention span. Therefore they would only supply one reel of film per week to member companies and they would only distribute films of that length. So because of the MPPC, audiences in the US were watching epic plays like King Lear or novels like Frankenstein boiled down to under 15 minutes.

However, the feature film was about to be born. In the US filmmakers like D.W. Griffith tried to distribute two reel films, one reel each week - which didn't work because of continuity issues. But, in other parts of the world filmmakers started making longer films and despite what Edison might have thought, the longer films captured the audience's attention.

Next article The Birth of an Art Form

Previous article A Shot in the Narrative

First article Before Film

No comments:

Post a Comment